Last week, for the first time, I watched the first movie I ever worked on, 25 years after its release.

That movie was The New Swiss Family Robinson, and the bootlegged YouTube version has over 4 million views. I found it to be what I expected: kind of corny, occasionally weird about race, and not made with me as the target audience. YouTube commenters generally have a nostalgic love for it. Rotten Tomatoes rates it 36%.

I probably spoil the film below, but you’ve had a long time to watch, and you can guess most of what happens from the title, so this is a warning but not an apology.

I’ll preface everything I’m about to say with the disclaimer that these are my most accurate memories of my experiences on set in 1997, which was a long, long time ago. I scoured the internet and corroborated at least a couple of the stranger aspects. I also re-read my embarrassing journal from that time, which I’ll quote, but mainly summarize to avoid exposing how petulant and entitled I was (at least in my inner monologue at twenty-one years old on 4 hours of sleep a night).

I’ve decided to keep a journal of the production since it sounds like a good source of the war-story film anecdotes no one can get enough of.

(This was the era of film students obsessed with the behind-the-scenes drama captured in films like Living in Oblivion; trailer below for Millenials and younger. :)

The New Swiss Family Robinson was my first time as part of a real movie crew (I’d worked on low-budget commercials and student films at art school). I was the “Sound Cable Man,” meaning I carried sound equipment onto and off boats, across beaches, and through rainforest locations.

Despite having a great deal of technical knowledge and creative problem-solving skills, the sound department is often one of the least-respected departments on a film set, and the sound cable person is the lowest-ranking person on the sound team. If anyone of any consequence on set was paying attention to me, it was because I was making a mistake. My perspective is in no way an “insider” perspective; it’s that of an (unwanted) fly on the wall.

All that being said, I think it’s entirely non-controversial to say that the production was a bonafide shit show.

The New Swiss Family Robinson was filmed in Puerto Rico, where I was born. Puerto Rico was the home my (very white) mom and (very white) aunt came to from college after growing up in Venezuela. It’s where my mom met my (very white) dad. I traveled there as often as I could. My aunt had a house in Old San Juan, and I loved my trips there, sometimes interning for her boyfriend’s gallery and digital studio, sometimes drawing storyboards for her ad agency, and sometimes just meeting up with locals my age and tagging along on nights of drinking, dancing, punk shows.

My role as Sound Cable Man was the one job in entertainment I received through nepotism. My aunt pulled strings to have me hired as a member of the Puerto Rican crew. As is typical when productions travel, department heads flew to Puerto Rico from Los Angeles. The rest of the crew was hired locally. That’s where my blonde-haired, blue-eyed, almost-no-Spanish-speaking self entered the picture.

I was brought on through the 2nd Assistant Director. He had a successful career in Puerto Rico as a 1st Assistant Director for international commercials for the Latin American market. He was working on the film to satisfy the requirements of joining the DGA.

Despite his fondness for my aunt, he was not confident that I brought much to the table (His instincts were correct. I brought nothing to the table) and drove me, along with a few other crew members, to set on the first day of filming so he could brief me on his expectations.

His expectations were low:

Show up with a smile.

Remember, it’s better than (real) work.

Do whatever your boss tells you.

He reminded me that I wasn’t part of the LA crew; I was part of the Puerto Rican crew, and he made it clear that those were two different loyalties.

And then he turned back to me and said, “No tengas miedo de hablar español.”

I swallowed. “Uh, what?”

The crew member riding shotgun shook his head in disgust. “He said, ‘Don’t be afraid to speak Spanish.’ You’re in Puerto Rico.”

“Oh yeah, right. Ok. Um, Por supuesto.”

No one else talked to me for the rest of the ride.

The 2nd Assistant Director had already warned me, through my aunt, that this production was going to be bad. The days were fourteen hours long, most of them in remote locations that would require a long commute to and from set (sometimes by boat). I would only be getting a couple of hours of sleep a night.

Rumors spread that the production was over budget before it even started because the line producer had based her assumptions on Mexican crew rates, not realizing that Puerto Rico is a Commonwealth of the United States with workers getting paid American wages. As production started, when I did have gossip translated for my benefit, a common refrain was effectively, “These fuckers think they’re in Mexico.”

The other phrase I would hear repeated from both the Puerto Rican and LA crew was: “Most movies aren’t like this. Don’t let this scare you away.”

I wasn’t scared. I’d been feeling stuck and was looking for something to shake me out of it. I wasn’t cut out for the military or the peace core, so I was seeking something like what I’d witnessed in Burden of Dreams, the documentary about Werner Herzog’s legendarily cursed experience making Fitzcarraldo.

I wrote in my journal:

I hope this will be a rebirth of sorts. This has been a very bad year for me. I planned extensively to shoot my degree project down here (Puerto Rico) only to find a general lack of interest/support here and at RISD. My junior (year) film sucked. My video teacher told me that my work was lame and I had a bad attitude.

My video teacher was 100% right about this. It made me sad not to have more, deeper friendships in my 20s, but I wasn’t offering much. RISD was fun, free, and gloriously queer, all things I was afraid to engage with. I mostly sat on the sidelines and occupied my mind with ideas because my feelings were too raw and messy to live with. It was the start of twenty years of staring down the essential question any artist looking to create meaningful work must answer: “What is the art that only you can make? What is the story that you are the best person to tell?”

You can’t answer these questions if you don’t know who you are. But, if you don’t know who you are, these questions are likely the least of your problems. I filled the void of my lack of self-knowledge with competency wherever possible. Most artists need people who know how to make the machines work. I was one of those people, always ready to fix a computer, a camera, a piece of sound equipment. I would be invited to other people’s film sets, and they would come to mine, within reason. But nobody thought a trip to Puerto Rico with me sounded like a good time.

So I came alone, looking to test my mettle. I wanted an experience chaotic to the point of transcendence (you can write this on my tombstone, along with “wish granted.”) Instead of Werner Herzog, I was under the leadership of Stewart Raffill, a director known for the “space comedy you didn’t know you were waiting to see” The Ice Pirates and E.T. copycat Mac and Me.

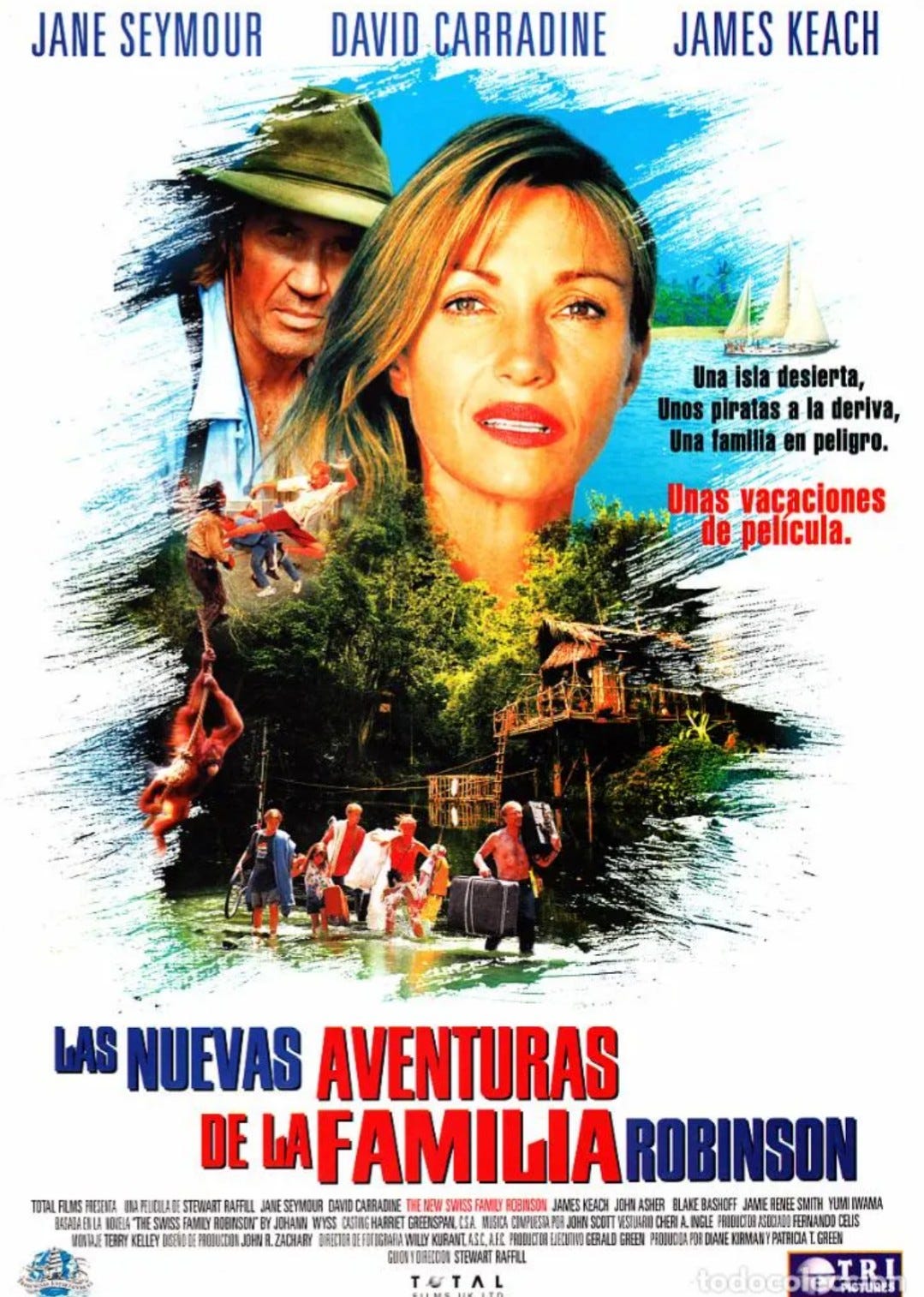

The New Swiss Family Robinson is an ensemble film starring Jane Seymour (famous “Bond Girl” and a household name as the star of Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman) as Anna Robinson and her then-real-life-husband James Keach as her on-screen husband Jack. David Carradine, who most famously played Bill in Kill Bill, plays Sheldon Blake, another villain - this one, a double-crossing pirate.

The Robinson children included John Mallory Asher as the “teen heartthrob” lead (he would go on to marry model, actress, and eventual anti-vaccine crusader Jenny McCarthy after starring in the TV adaptation of Weird Science), his younger brother played by Blake Bashoff (Karl Martin, from Lost), and his younger sister, played by Jamie Renée Smith (Kimmi, from Weeds).

Blake and Jamie Renée were children, and I didn’t get much of an impression of them, except noticing how the production didn’t appear to be particularly invested in their well-being.

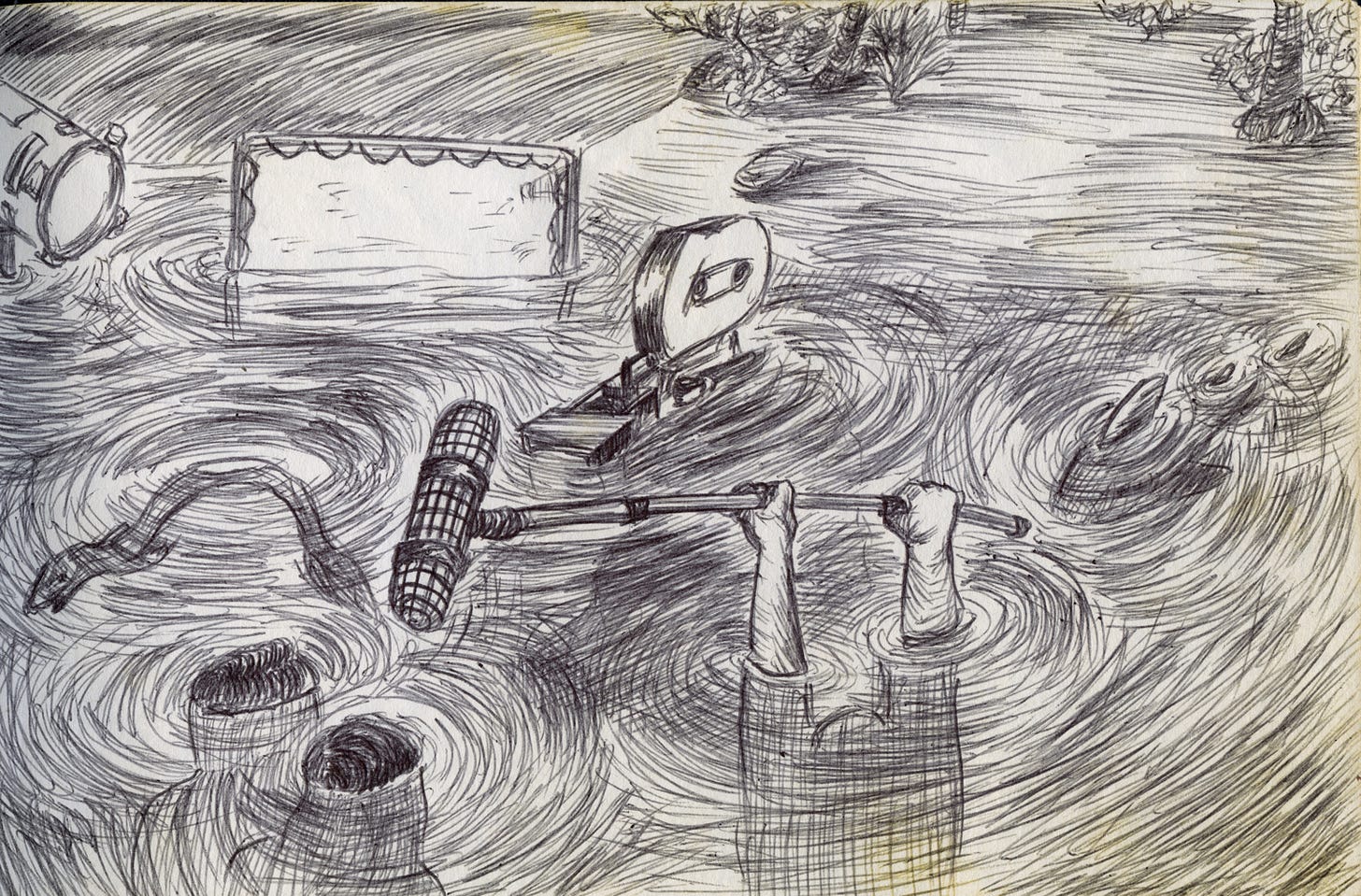

Early in the production, we were filming a scene in which the family Robinson was searching the wreckage of their ship. My job was to hold a small inflatable dinghy in place so that the sound recordist and boom operator had a platform to operate from. Effectively, I was a human anchor. Puerto Rico is a beautiful place with perfect beaches and clear water. We stood in chest-deep water, fifty feet from shore, and could look down and clearly see our toes in the sand.

When I felt a bump against my leg, I could also clearly see the 4-foot shark that nudged me. And I could see several others, some larger. There was a moray eel, too, hunting near the actors.

I’d never been to LA, but the 1st Assistant Director embodied all the qualities I associated with “LA people.” He was fast-talking, told people what they wanted to hear, was quick to assign blame, and had a loose relationship with the truth. He also didn’t think much of me, which made it easy for me to overlook whatever redeeming qualities he had.

When I saw the sharks and the eel, I subtly got the attention of the first AD and managed to draw his attention to the animals in the water. He clocked the sharks and the eel swimming around the kids’ legs and looked back at me. He put his finger to his lips in a silent “shh.”

At the end of each day, the crew left on boats that could only take a few people at a time. The boats shuttled back and forth, and it was hours between the first boat out and the last one. The cast left first, then the LA crew, then the Puerto Rican crew. The sound team had less equipment than most of the crew, so my boss and the boom operator could occasionally get out on an early boat. I joined them once or twice but often stayed behind and rode out on the last boat.

Mainly, people worked and chatted in Spanish, but when the gear was sorted, they’d smoke weed, waiting for the boat to come and catch me up on the best of what I’d missed. This is when I’d hear about how much they hated Jane Seymour for her disrespect, how much they hated Willy Kurant, the cinematographer, for his temper, and how much they hated the 1st AD for his general sleaziness. Occasionally, other villains from the LA crew would enter the rotation.

In after-hours chats, I learned that the camera department had repeatedly lost rolls of exposed film, meaning that we’d be reshooting whole days of production. This was terrible news on any movie, but all the more on a film like this where nobody had enjoyed the scenes the first time we shot them.

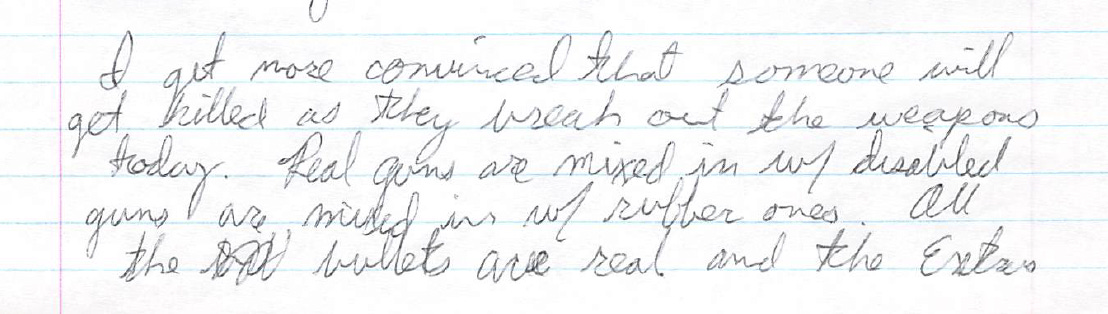

Everything was a little unhinged. The animal wranglers were sketchy. The armorers and stunt team, too. This was before Halyna Hutchins was tragically shot while filming the Alec Baldwin film Rust, but as someone who grew up with guns, the easy access to real guns with live ammunition terrified me:

I get more convinced that someone will get killed as they break out the weapons today. Real guns are mixed in with disabled guns are mixed in with rubber ones. All the bullets are real.

One scene's “visual effects” consisted of a stuntman firing live rounds from an M-16 assault rifle into river water a few feet away from another stunt performer.

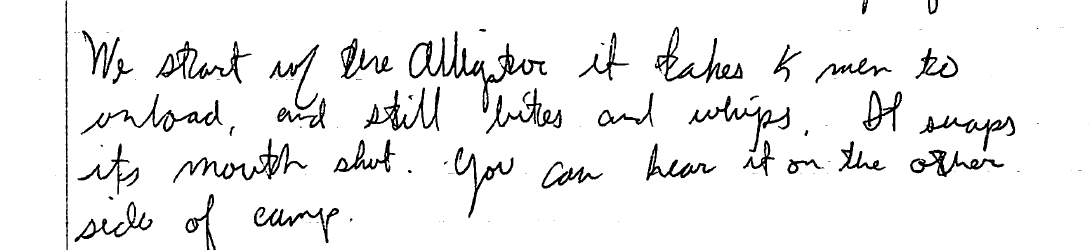

The animals were equally sketchy. Giant iguanas brought in to act as props in a scene swung their spiked tails at anyone who got close to them. When another scene called for live alligators, it was clear that the team wrangling them was short-staffed:

We start with the alligator. It takes 5 men to unload and it still bites and whips. It snaps its mouth shut. You can hear it on the other side of camp.

Not all of the chaos was dangerous. Some of it was just chaotic. When we started filming, there was a whole subplot dedicated to the teen heartthrob character falling in love with a red-headed French girl whose parents had died in a plane crash on the island. (She’d been raised by orangutans, because why not?). Before he meets the girl, the whole Robinson family teases him that the “redhead” is actually a local orangutan.

The cast seemed to like the actress who played the redhead. I suspected she and the teen heartthrob had an on-set romance. But then, one day, she was gone - replaced by Japanese-American actress Yumi Iwama. It was never explained to the Puerto Rican crew why the swap had been made. Clearly, the rest of the cast didn’t like this replacement. “The redhead” became “The Asian” off-camera, and “The Asian” was the only way they referred to Yumi when she wasn’t around.

Less dramatic firings and replacements were a regular occurrence: the film loader, the Steadicam operator, and the script supervisor all vanished to be replaced by fresh faces flown in from LA.

As we fell further behind schedule, rumors began circulating that the bonding company was considering shutting down the production. I didn’t know what this meant, but it was explained to me that if a movie goes far enough off track, the company insuring the production for the studio will take over, bringing in their own team to do the absolute minimum to fulfill the obligations of filming the script. When they do this, they replace the director. That director becomes uninsurable, effectively ending their career.

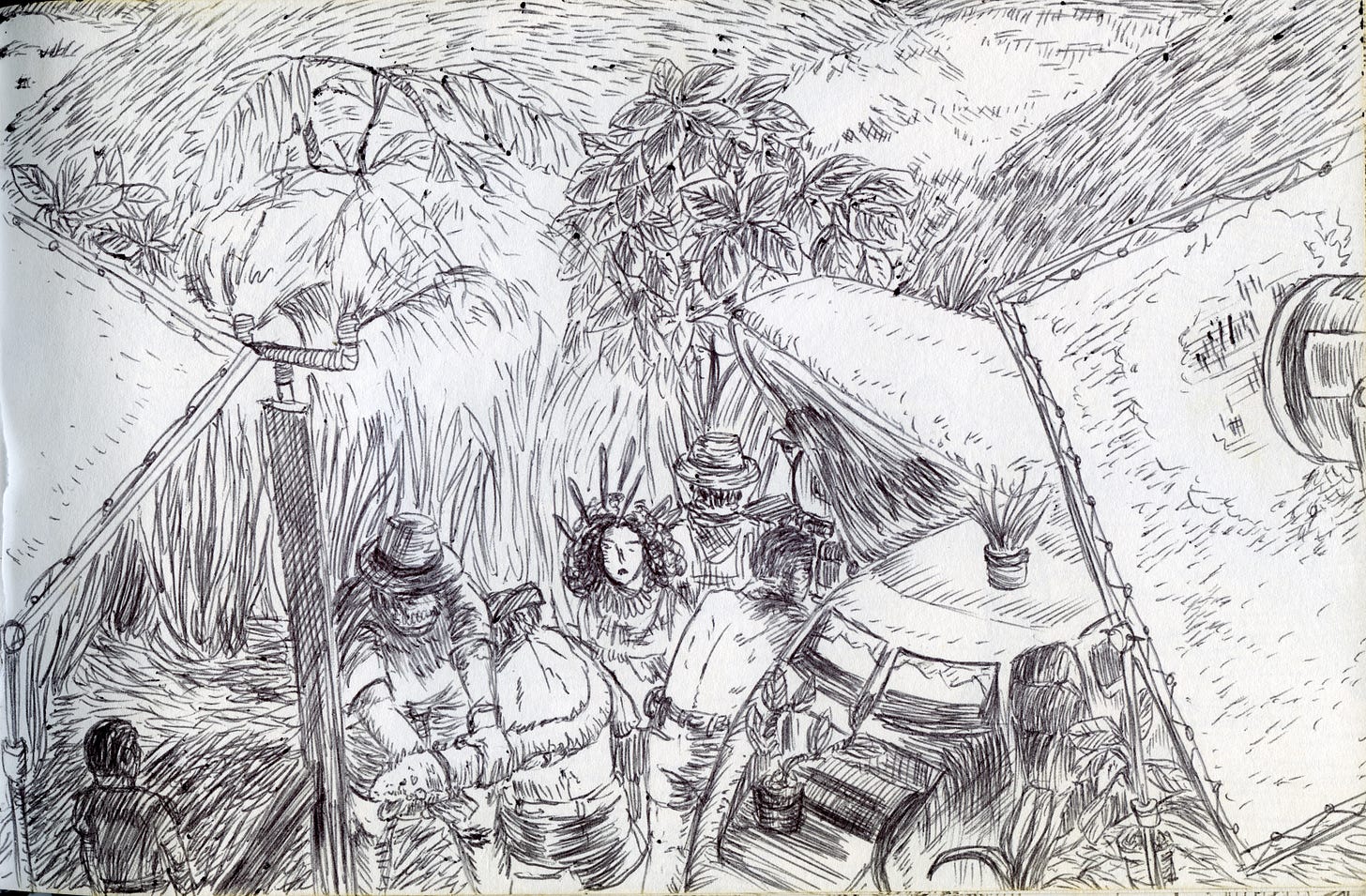

The day that was explained to me, I wandered off into the rainforest to eat lunch by myself and draw in my sketchbook and found Stewart Raffill sitting by himself, holding his head in his hands. Stewart was usually tall, charming, and funny. In my journal, I write that he was “mumbling to himself in Spanish” (I think practicing to directly communicate with the Puerto Rican crew with more love than Willy Kurant showed them), but I don’t remember that. I remember how sad he looked and thinking I’d never seen a grown man looking that sad.

A true film student, I ignored his sadness and asked him if he had any advice for an aspiring director.

He told me: “Most movies aren’t like this. Don’t let this scare you away.” (I didn’t. Maybe he was my Werner Herzog after all?)

Along the way, I became friends with the crew, mainly bonding over relationships. A mentor figure on the Puerto Rican crew confided to me that his marriage was falling apart; the long days we were working were the nail in the coffin of his marriage. When I asked him why he didn’t quit this nightmare of a production, he said if he quit he wouldn’t be able to afford his divorce. A young, macho Production Assistant from the LA crew was falling in love for the first time with a girl back home. It was the first time he was saying “love” and was having a personality crisis after identifying as a player. I was using expensive phone cards to get into long-distance arguments with my college girlfriend about drama. She was considering applying to UCLA for graduate school. “That could be good for both of us, right?” My only lens for LA people was the sampling I’d met in Puerto Rico; they were not selling me on the city.

Things got stranger. There was a grip with beautiful, piercing eyes who didn’t speak English. He didn’t talk much in Spanish, either: just terse clarification about equipment - the length of a piece of dolly track, the size of a stand. He said a lot with those eyes, though. I found myself watching him for reactions to the chaos and disrespect. The subtle disapproving shifts in his expression were somehow more devastating than the overt shit-talking from the rest of the crew. He would smile when he caught me catching him.

When we were based on a small island resort, the production took over a few sheds as storage. This was a blessing, as it meant the equipment could be left overnight, saving the crew hours of loading and unloading. It was time we could sleep. One day, the sound recordist sent me to the shed to borrow an apple box for the boom operator to stand on. Inside, I found an elaborate altar: candles, Catholic icons, a headless black-feathered chicken, its feet cut off and tied with string into a spidery and magical assemblage.

The silent grip caught me examining his work, handed me an apple box, and that was that. When Jane Seymour contracted dengue fever, I wondered if he’d put some unkind magic on her. Now that I know more witchy people, I don’t think he’d risk that spiritual negativity on avenging diva behavior.

When we later got caught in heavy rain, loading out equipment on a treacherously narrow path in the El Yunque rainforest, the silent grip nodded toward the knife on my belt. I gave it to him. He pushed his knife and my knife into the ground and looked to the sky. The rain stopped. It was magic that a very cynical, skeptical me felt at a time when I didn’t believe in those kinds of things.

Time accelerated, and locations melted together in a fever dream of impossible days without enough sleep. At some point, I remember that we paused production for a week because of the dengue fever or the bonding company, or who knows?

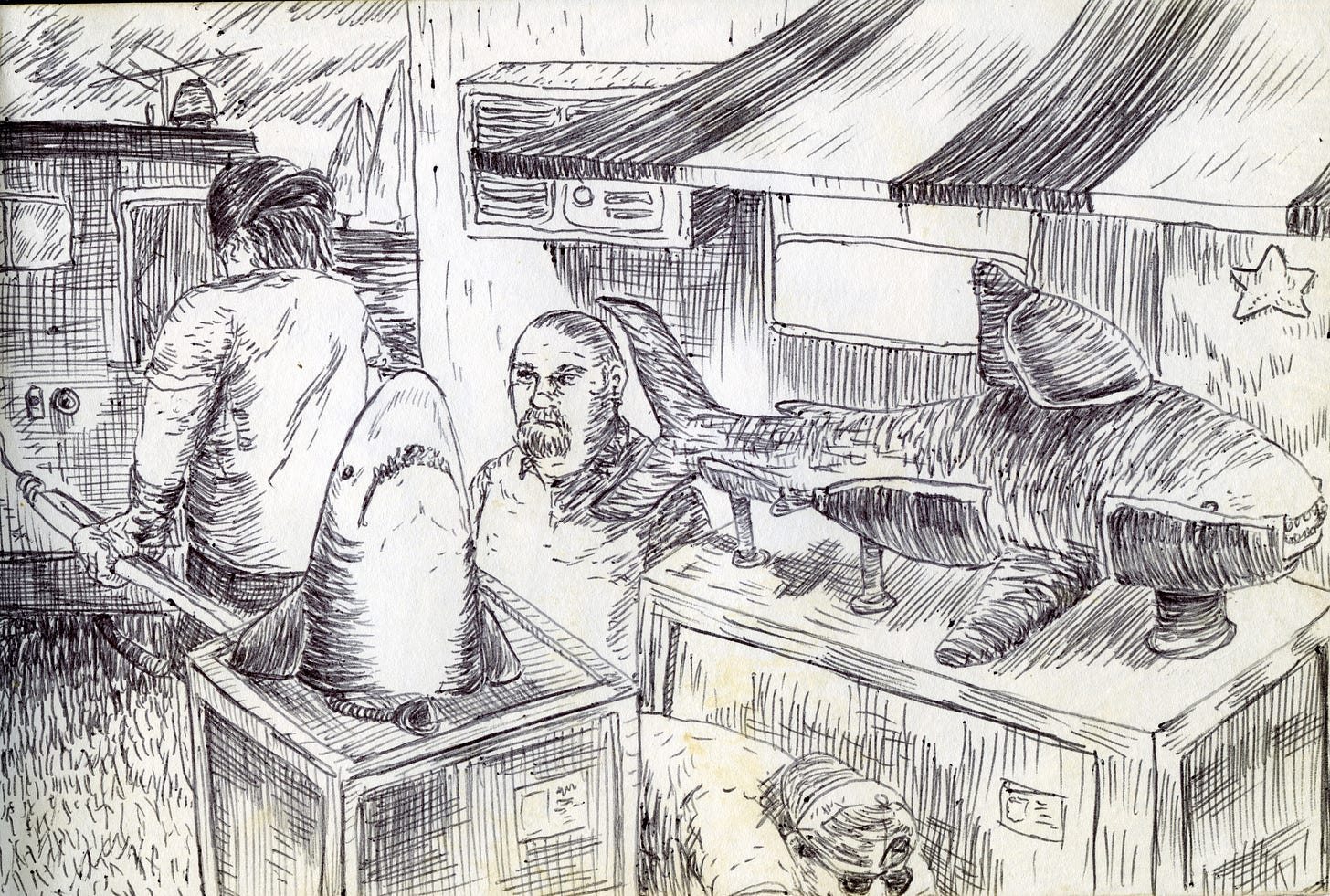

We filmed pirate battles while Jane Seymour fought off the virus. We spent days on a tuna boat that had traveled from Florida for the production. It felt good to be around other Southerners who shared my suspicion of the “LA people.” Once, we used a Navy base as a location, and at the security checkpoint, one of the crew members yelled to the American guards, “¡Tenemos una bomba!” (“We have a bomb!”) and they waved us in, unbothered. The Navy base had strict rules about litter, and looking into the pristine water from the dock was like looking into an aquarium. Cuttlefish swam right up to us and put on fantastic alien light shows with their psychedelic skin.

Our scenes with David Carradine weren’t filmed until the end of the production, and he brought the bizarre presence you might expect from Kung Fu or Kill Bill. I think the only thing he said to me on set was, “Don’t cover the ink, man,” when I closed his shirt to get a wireless microphone closer to his mouth. I have not been able to corroborate this, but I remember that he changed in front of the rest of the cast and the crew and that his buttocks were tattooed blue. The closest I could get was this perfectly titled National Enquirer article (“The Secret Psychotronic World of David Carradine”), which suggests that:

Despondent over his father's death, Carradine attempted suicide by shooting himself in the scrotum with a blank gun. And…

This injury damaged a perfectly good tattoo.

Maybe it was his tattooed scrotum I saw?

Is there any circumstance in which the National Enquirer is an acceptable source, even if to corroborate a bizarre half-memory? Carradine was so visibly on his own wavelength, emanating power and pain and keeping the circle around him small. A seeker and weirdo, which I mean as compliments. I didn’t envy whatever experiences earned him his intensity.

Jane Seymour recovered. We shot the beginning and the end of the film, everything with the family Robinson and villain David Carradine. First, a send-off from a San Juan marina doubling for Hong Kong. Then, the climax of the film as the men of the Robinson clan battle for (and ultimately gain) control of the pirate ship while the women (Jane, Yumi, Jamie Renée, and the orangutans) escape from the heavily armed pirates coming to kill them… for their treasure, I think? It’s something like this. This is a movie where the bad guys probably could have won if they had an hour-long conversation to clarify their priorities and make a loose plan.

Once the men jettison all the pirates from their boat (all the actual tuna boat crew members got cameos as pirates, and you could tell they were having a lot of fun), and the women successfully steal a motorboat and avoid actual and on-screen death by M-16 rifle fire, the script called for a scene in which Jane lifts her daughter and Yumi from the small boat to the big boat, and has a tearful reunion with her family. As written, it was Jane’s big emotional moment - some real acting in a family film that didn’t call for much.

In reality, the day was a nightmare. The ocean was choppy, churning most of the cast and crew into intense seasickness. Choreographing cameras, two boats, and the safe transfer of two adults, a child, and several orangutans sounds complicated and is way worse than it sounds. If a take got off to a bad start, it took half an hour of puking, miserable boating to reset everything and make another attempt. The sky was polka-dotted with clouds, which would change the light completely from minute to minute. Willy Kurant stared through a tinted monocle, making a best guess of when we should put the complex operation into motion so we’d get consistent light throughout the shot.

Countless false starts and much seasickness later, everything aligned. The motorboat glided to the side of the tuna boat and safely secured itself for disembarking. Out climbed Jaime Renée, out climbed Yumi, out climbed the orangutans onto the large frame holding a silk over the scene to diffuse the lighting. And then came Jane Seymour, fully in character, bringing all of her star power to this pivotal moment at the heart of the film. And, as she started, from above her, an orangutan peed on her head.

The crew laughed. Jane expressed her frustration. All the intense effort and ludicrous calamity of the last few weeks culminated in a shot that the audience would never see. In the final film, we see the motorboat reach the tuna boat, unload Jaime Renée, and immediately cut to a shot of the Robinson family happily reunited. The orangutans are behaving themselves:

Because of the delays, I had to leave the set to return to my senior year at RISD before principal photography was completed. My aunt told me that production stopped in Puerto Rico before the movie was fully in the can. I later heard through someone in the camera department that they were shooting a week of pick-ups in LA to complete the film. When it finally came out, I could never figure out where to watch it.

Years later, I coincidentally ended up on set in Miami with that same camera person. He told me he’d heard that the jaguar wrangler for the Los Angeles shoots had lost his arm because the director insisted on an unsafe take. Some heavy Googling pointed me to “Trained but not Tamed,” a 2001 article from Moab Happenings (“Southeast Utah’s Events Magazine”) about Terry Moore, the wrangler. He was bitten on the leg, not the arm, and doesn’t mention losing it:

In the twenty years that Terry has been in the movie business, he has only been bitten four times. Every one of those instances could have been avoided and were usually the case of an extra stunt or “shot” that went against Terry’s instinct and better judgement. It is always human failings that cause mistakes. In the film “Swiss Family Robinson,” Terry does a chase scene with a black jaguar. These types of scenes run the risk of the cat, bear or whatever doing the chasing, becoming “turned on” by chasing prey or the baiting act. In these types of scenes, Terry says that there is a cool down period right after this type of shot. But the director liked the stunt so much that he wanted one more shot, and though Terry didn’t feel right about it, he agreed. In this particular instance, the animal handler and Terry ended up prying the jaguar’s jaws off Terry’s leg. Mind you, this isn’t just some jaguar that is brought on a set from out of nowhere.

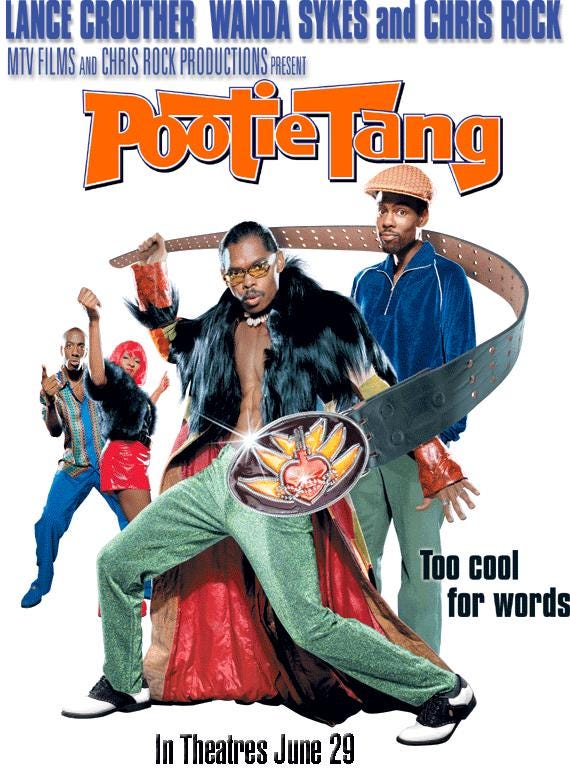

Much later, I ran into our ill-tempered Cinematographer, Willy Kurant, at The Grove, a classic LA outdoor concept mall. By then, I’d looked him up to see what he had shot before The New Swiss Family Robinson and what he’d shot since. I learned he was a cameraman in the French New Wave and lensed films directed by Agnes Varda and Jean-Luc Godard. Since we worked together, he’d shot Pootie Tang, a classic in its own right.

I reintroduced myself and reminded him that we worked together in Puerto Rico and that it had been my first real movie. He laughed. “And you’re still doing this? Wow!”

Since The New Swiss Family Robinson, I’ve worked on a few other dysfunctional sets (one or two have been mine, and I’m sorry). Luckily, most have been significantly more professional. Nothing about all that chaos scared me away at all. It opened my eyes to an industry full of adventurous people going to interesting places and forging intense summer camp friendships. I had never really connected with team sports, but on set, I loved the feeling of dozens of different kinds of artists and technicians coming together to make something. Even if the “something” wasn’t high art or blockbuster entertainment. I learned it’s a minor miracle that anything at all gets made.

I’ve even gotten to make good things that people have seen and loved. I think those experiences mean more, having been a tiny cog in a broken machine that produced something most people didn’t see or love.

When I returned to RISD from The New Swiss Family Robinson, my attitude still sucked. My senior film wasn’t great, either. But, I kind of, sort of had a vision for what it might feel like to make good things with happy people.

I hadn’t been reborn. But I’d learned something that would stick: