I Tried to Write Something Smart About Tattoos

Needles, Ink and the Rush of Bodily Autonomy

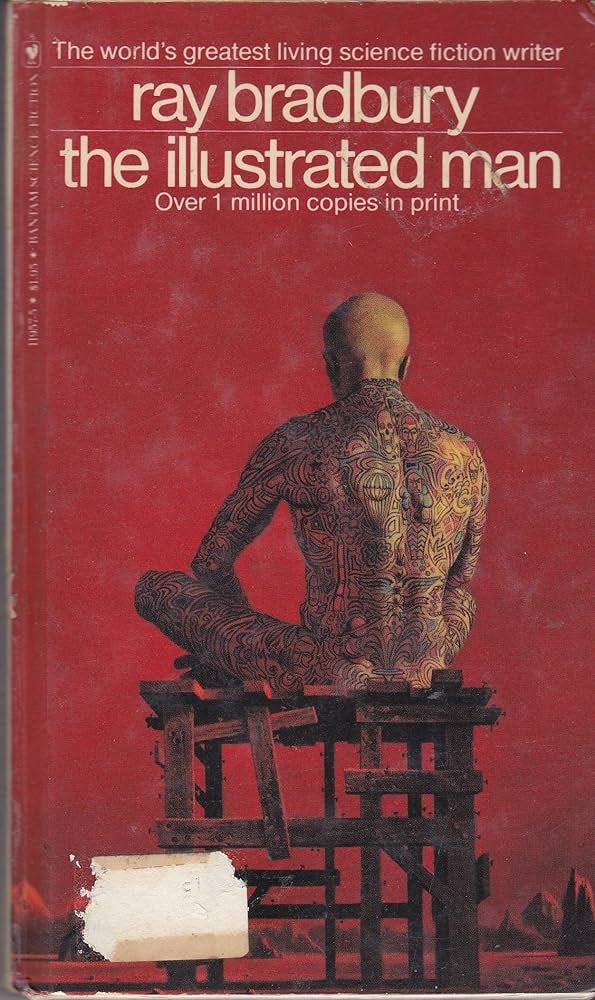

I first understood how badly I wanted to be heavily tattooed in elementary school. The school library had a paperback copy of The Illustrated Man, a book with stories that I didn’t respond to at all but nonetheless renewed repeatedly so I could look at the illustration on the cover. I wanted to be like that, covered in art, my body something I designed.

This was in the ‘80s when tattoos were still socially unacceptable, the domain of rock stars, bikers, and Vietnam vets.

Growing up, my mother was partial to class-based epithets, using “LMC” (Lower Middle Class) as a pejorative for things she found tacky and referring to my blue-collar friends at the fringes of our neighborhood as “apartment rats.” It was an aspirational snobbery, a good fit for the Reagan-era obsession with status and upward mobility, but out of sync with our lived reality. In those years I wore mainly clothes from K-mart that my grandmother stockpiled for me at the end of summer vacation.

Those clothes were one of the many things I was bullied for. There was a whole routine around it, which I fell for more than once:

Preppy kid: “Oh wow, I used to have that shirt!”

Me, excited to be connecting with someone socially out of my league: “Yeah? Really?”

Preppy kid: “Yeah, and then my dad got a job.”

(Laughter all around, no one louder than me. After school, I would throw away whatever shirt I’d been wearing, burying it under other kitchen trash so no one would see.)

Actually ever getting tattooed felt impossibly taboo. I imagined it was something I would do when my parents and grandparents died, and there was no one left to be ashamed of me. I didn’t want them to die, of course, but that seemed like the only way I’d ever have the opportunity to do something so frivolously, selfishly transgressive without dishonoring both sides of my bloodline. It felt impossibly far away, but so did everything else in adulthood. Tattoos would come after driving and voting, but before grandkids, probably.

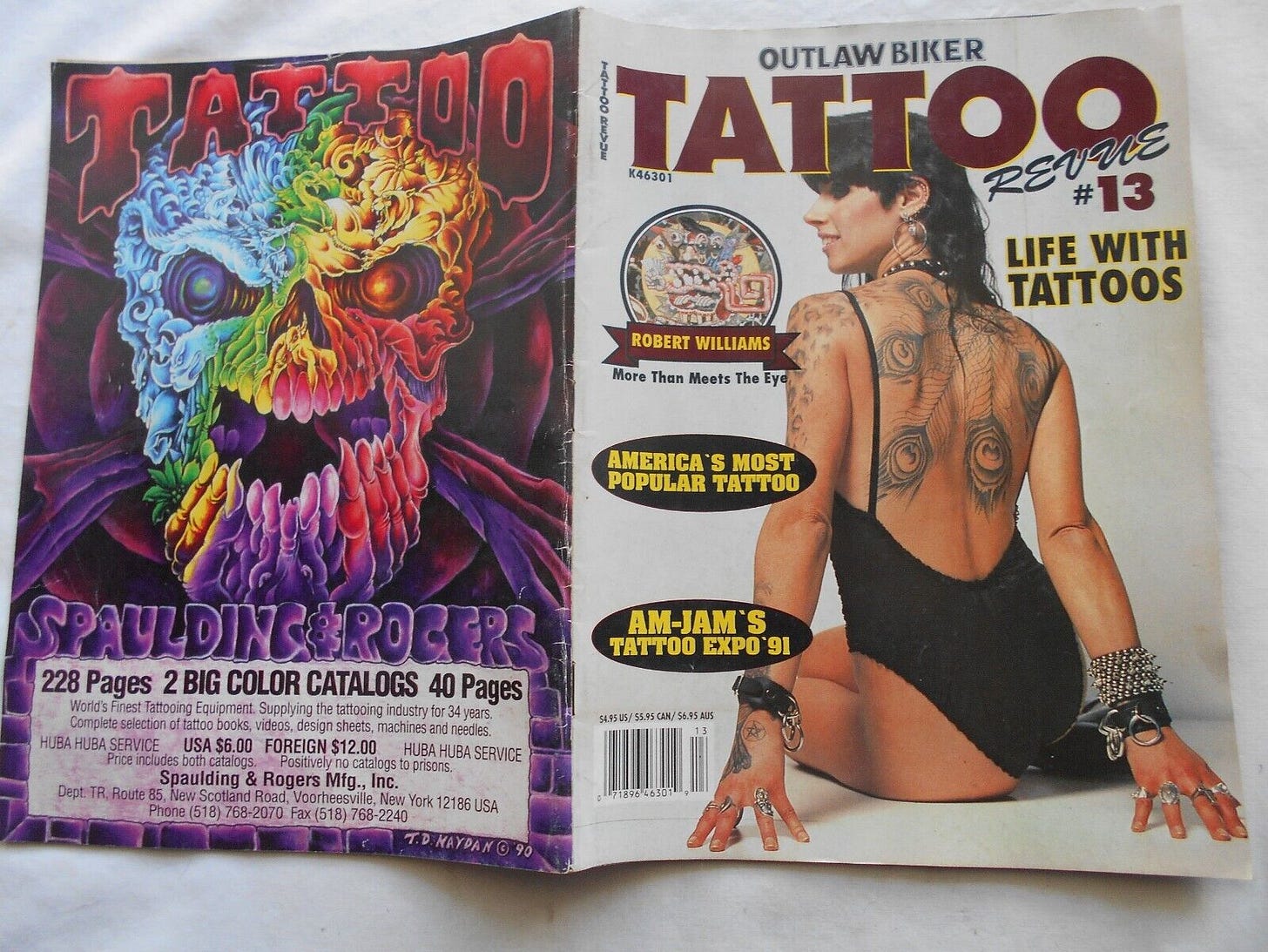

Only the itch didn’t go away. It got stronger in the '90s in high school when I had a little money; I’d buy copies of tattoo magazines at 7-Eleven. I didn’t love most of the art in Outlaw Biker Tattoo Revue or Skin and Ink. It was an era of a lot of chrome skulls, a lot of bad copies of the kind of bodysuits Japanese gangsters in the Yakuza wore, a lot of Confederate flags and iron crosses, a lot of shops with “Z’s” in their names where “S’s” should have been.

I loved the portraits of tattooed ladies like Maude Wagner and Jessie Knight. Smiling across the decades in black and white, they were fearless in ways I couldn’t comprehend. What would it feel like to be like them? How cool would it be to prioritize my preferences over the judgment of strangers? I knew I could never. Nonetheless, they were heroes to me in ways I couldn’t quite grasp. It was a quintessentially trans experience - infatuation with people you’re not sure you want to be or become.

The courage of these women to be so visibly themselves in a time so oppressively discouraging of that impulse gave me courage of my own.

I didn’t wait to be orphaned. I got my first tattoo at 16 years old. I was visiting my Aunt, who lived in Old San Juan, Puerto Rico, in an ancient house on a cobblestone road. She worked in advertising and was gone all day most days, leaving me to explore the city, taking photographs and trying to buy things with traveler's cheques because I’m exactly that old.

Two areas of Old San Juan were placed off limits to me: La Perla, the massive unincorporated squat-filled community on the north side of town, and Luna Street, which was at the time a red light district. La Perla was easy to avoid, set off from the rest of the old city, and - at least then - palpably not a place looking to host a tourist with a camera. But, as I wandered through the old city, I kept ending up on Luna Street.

Described by my parents, a street full of prostitutes sounded frighteningly alien. Walking around Luna Street was a new experience, but the sex workers weren’t scary. This was probably the first time in my life I encountered people I recognized as trans. The girls flirted half-heartedly, but I don’t think I really seemed like a prospective customer. The truly scary thing about Luna Street was the floating vampiric presence of heroin addiction and the accompanying specter of AIDS. The girls were skinny, erratic, desperate in a way I hadn’t seen in Texas. I wasn’t scared of them, but I was scared for them.

Amidst all the girls on Luna Street was a tattoo shop, and as soon as I saw it, it clicked: I bet they don’t card there.

I brought in a drawing of a sunflower from a Houston jam band I was obsessed with despite primarily being a grunge fan and metalhead. The artist quoted me a price (I think $60), and we made an appointment for the end of my stay in Puerto Rico. I asked him if he would accept a traveler’s cheque, and he looked at me like I was the stupidest person ever born.

For a few tense days, I tried to use the biggest possible traveler's cheques to pay for the smallest possible purchases, making myself very unpopular at many cafés, restaurants, and souvenir shops and stacking the cash I needed for my tattoo.

When the time came for my appointment, I had just enough cash. I was giddy until I rushed excitedly down Luna Street past all the girls and saw their scattered sores, their scratchy tattoos, and their skinny heroin bodies and thought: what about AIDS?

I asked the artist how he kept things sterile. He looked at me like I was stupid again, pulled a wire coat hanger from beneath the counter, and lit a soldering torch. He held the bottom of the hanger over the torch and pulled the ends slowly, splitting the metal into a fine point, which he snipped off and sharpened further on sandpaper. He looked at me; telegraphing is that good enough for you? It was. HIV was scary, but I was vaccinated for tetanus.

The artist asked where I wanted the sunflower, and when I told him I wanted it on my left hip, where my underwear would cover it, he warned me that a sunflower on my hip was, objectively, a pretty gay tattoo. I told him not to worry about it, and I felt a rush not caring about what other people thought. Thirty minutes later, I had my first tattoo.

Walking back down Luna Street, I was giddy. I felt cool, which was a new thing for me (and is still pretty rare). What I’d done was dangerous and sexy and brave. I went home to my aunt’s house and stripped before the bathroom mirror, admiring the inch-and-a-half-square of myself I’d somehow claimed. It was a rush like nothing else I’d ever experienced. I didn’t belong to my parent’s expectations or my grandparent’s shame. I didn’t belong to the middle school bullies who would have tortured me for this permanent and audacious faggotry. I belonged to me.

I got my second tattoo the week I turned 18. I paid for them with a few hundred dollars in two-dollar bills I’d been saving from my grandmother’s birthday presents

I had been interning at an ad agency before the internet when stock photography was kept in three-inch-thick hardcover books full of glossy printed images organized by theme. There were pages and pages of staged meetings full of executives at varying levels of diversity, levels of stress, and demonstrated camaraderie. There were whole books full of a very specific kind of attractive but not particularly hot people on vacation: solo, in heterosexual couples, and cautiously platonic same-sex groups. And then, because it was the 90s, there were the “alternative” stock images. As a teenager, I didn’t have cable, so I only got MTV by proxy. I loved SPIN magazine and the artsy, incomprehensible zines that were always too smart or too weird for me to absorb as more than an aesthetic to quote, hoping there would be no follow-up questions.

The “alternative” stock photography book pages were my Tumblr - a moodboard of context-free grunge and punk gorgeousness. Here, there were the highly body-modified people I’d seen in the Jim Rose Circus Sideshow, models on the chic side of heroin addiction, artists, scumbags, hippies, and Bohemians living lives I would never, ever be brave enough to try. But, like the tattooed ladies, these stock photo Seattleites still inspired me.

There was one spread I wish I’d had the courage to steal: a black and white series of a woman in nature, wearing a vintage dress and stepping into a stream. In one close-up, she tiptoed into still water, revealing delicate flowers tattooed around her ankles and on the tops of her feet. They were beautiful, feminine, and romantic, sure, but also: they could be covered by socks, and I could conceal them from my family forever.

I designed my own version of these tattoos, replacing her flowers with moons and stars from a Babylonian vase in an art history book - symbols representing Ishtar, whose 5th-century BCE temples were kept by transfeminine priestesses. I vaguely remember romantic notions of these tattoos symbolizing walking in the stars on an ancient, holy path that I didn’t understand. Now, that reads like dramatic irony. Then, I was just a weirdo without a guiding aesthetic.

My second tattoo shop was slightly less sketchy than the first. It was in a strip mall beneath the spaghetti bowl of I-10 and Beltway 8 in Houston, wedged between a sex shop, a head shop, and a fortune teller. I picked the place mainly because it seemed (and was) cheap. The clientele were mostly bikers and rednecks. The artist’s portfolio was heavy on Yosemite Sams, cross-eyed pinup girls with their tits out, and flaming zombie biker skull creatures flashing middle fingers, waving the stars and bars, or - for the right price - doing both. I only remember that he looked like exactly the guy you would cast to play “dude who does cheap tattoos for bikers next to a dildo store” if you were filming that episode of Sons of Anarchy.

When I paid upfront with a stack of $2 bills, the artist shot me a familiar look that suggested he thought I was the stupidest person in the world (Oh my god, I know - right!? At least they aren’t traveler’s cheques!). He asked if I worked at a strip club. I stared at him, not getting it. He said that strippers got tipped in 2s. I told him I was not a stripper. He told me that the tattoos I was about to get were “Some faggy ass shit, but I’ll do it if you want. On the feet is going to hurt like a motherfucker.”

He was right about everything. He had a heavy hand, and my faggy ass tattoos were excruciating, alternating between the awful snare-drum rattle of the needle on ankle bone and torturous scraping as he dragged the needle across the sensitive tendons on the top of my feet. He gave me the yellow pages and told me to twist it as hard as it hurt. This, unsurprisingly, did not help.

It was a Friday night, and it was payday. The shop was filled with regulars with money to spend on Yosemite Sam tattoos. They drank at the counter, watching me getting my faggy ass foot tattoos. They made racist jokes, said horrible things about women, and occasionally commented on the irony that I was undergoing so much pain to look like a total pussy.

I left hours later, woozy from the pain and, despite all the homophobic feedback, thrilled with my transgression. I drove home and carefully pulled on socks to hide my crime.

My mom was waiting for me when I arrived. I had lied and said I was spending the evening with my friend Jimmy, but I hadn’t filled him in on the lie, and he’d called the house looking for me. When I slunk through the front door, she hissed, “Where have you been?”

I said I’d been at Jimmy’s but quickly came clean.

“Let me see them.” She said, with the gravity of someone investigating a murder.

I showed her my feet, and she wailed a terrifying animal sound. “You ruined my baby!’ She howled. “You desecrated your body! Now you look like some faggot from Montrose.”

I laughed at this. “Mom, that’s crazy. No gay man would ever get these tattoos. I copied them from a woman.”

She proceeded to punch me, which I’ve written about here. She chased me up the stairs, throwing wild closed-fist hooks and slaps at my face as I laughed at her for not being better at fighting. Many threats were made about throwing me out or not helping me with college expenses. Eventually, I locked myself in my room and listened to Rice University campus radio to drown out the dramatic sobbing from downstairs.

In my room, I lay in bed looking at my feet, listening to Laurie Anderson and Jello Biafra, and feeling the rush of having claimed a few more square inches of myself.

My mom sent me to stay with my grandparents for a few days. My grandmother said the new tattoos were pretty, but why hadn’t I gotten color? My grandfather asked how long tattoos last and laughed when I told him, “Only until you die.”

Over the next 24 years, I claimed myself a few square inches at a time, first with slightly better tattoos in slightly less sketchy shops.

Several people’s names were etched into my skin, only to be covered later. I expanded and colored in the sunflower in a more extensive, more hippie-dippy design. Not long after, I flip-flopped and decided I hated the flower for its femininity and what it said about me. While working on my first-ever movie job, I went to another tattoo shop in Old San Juan to have it covered over with a six-inch black square, which sat on my hip for years, looking like a permanent pocket until I had it covered with an even larger black rose.

In midlife, after my grandparents passed, and I found myself increasingly uncomfortable in my own objectively great life and confusingly alien body, my tattoo collecting accelerated. By then, tattoos were socially acceptable, part of the uniform of a whole generation of creative professionals who’d come of age after the era of appropriative “tribal” tattoos and spring-break tramp stamps.

Still, I “kept it corporate” for a long time, wearing long sleeves in most circumstances as the tattoos crept down my arms and legs and covered most of my torso. They weren’t really for anyone else, anyway; they were for me. But on a hot set one day, I unveiled them, surprising a crew that had to quickly recalibrate their mental image of me to be however less square the tattoos made me.

Even though the tattoos were now acceptable, I wasn’t ready to be seen as ‘different’ even if ‘different’ no longer meant ‘outlaw biker’ and now meant ‘graphic designer’ or ‘barista with a philosophy Ph.D.’

But when you get to the point where someone asks you how many tattoos you have and your honest answer is, “I lost count a long time ago,” being different is part of the ride. When he was five, my oldest son told me he’d never get tattoos because they were “too show-off-y” which I didn’t necessarily disagree with, but I remember trying to tell him that was my least favorite part of them.

I lost count of how many strangers asked me if I was in a band, how many acquaintances were surprised that I’d never really done drugs, and how many friends tried to conceal their surprise when I revealed how few people I’d slept with. There was a marked disconnect between the person my tattoos told the world I was and my lived reality.

There was something about this dissonance that helped me push through the secret of my transness. Looking like a non-disabled straight white man, I didn’t have many opportunities to experience being different from an acceptable “norm.” Tattoos gave me the tiniest taste of the frustration of being perceived a certain way because I looked a certain way. But, let's be real, there are worse misperceptions than a fictional history of sex, drugs, and rock n’ roll.

When I started living publicly as a trans woman, I hated my tattoos. The last thing I needed was something else to make me seem different. The only thing in the world I wanted was to vanish into basic bitch obscurity, to be the most forgettable middle-aged suburban mom in the history of the genre. Walking through a Ralphs with a bald head, sleeved out arms and legs, and a tasteful tinted lip balm is not a formula for anonymity.

On a long walk with my dog, I was wearing a hat and a tank top when a man in a Dodge Charger pulled up next to me, parked, and jumped out to flirt with, “Hey… Where’d you get all those tattoos.”

As he got closer, I could see him realize that I was trans, and I was weirdly grateful to him for half-heartedly continuing his flirtation with me even after he realized that I wasn’t what he imagined.

What do you call the combination of unwanted attention and trans allyship that comes when a bro with a muscle car chokes out the words “So, you got those all over?” while trying his hardest not to imagine what my ‘all over’ looks like and what that might mean for his hetero cred? People with better intentions have said worse to me. I hope he’s out there thriving with an inked-up cis girlfriend.

I’m back to loving my tattoos. As it turns out, all that time in a chair, having needles thrust into my skin was good practice for my 300+ hours of electrolysis, 5 surgeries, and 6 hair-transplant procedures and all their accompanying blood and discomfort. Pain is not a friend of mine, but we’ve spent so much time together that I’ve gotten very good at sitting with her.

Now that I spend a lot of time in public as someone different from 99% of the world, I’m grateful for the experience of being misunderstood for reasons that felt a little safer. Tattoos were my training wheels for being kind of a freak.

And who doesn’t get misread in this world? Who isn’t a vessel for other people’s misperceptions? Now that I live as my heavily tattooed, visibly trans self, I’m more aware of all the ways that there’s no way to be beautiful enough, able-bodied enough, well-dressed enough, or “normal” enough to be understood. The older I get, the more I give up on even attempting comprehension, the more I value being the author of an existence so consistently misinterpreted, and the more grateful I am for the handful of people who see me and understand.

Great essay! I got MTV in Laredo Texas because it was broadcast over the air in Mexico for some reason. Thanks for the memories.