I pulled on a fresh diaper, locked the Airbnb, shuffled onto a donut-shaped surgical pillow and ice pack in the driver’s seat of my Subaru, and took a breath, readying myself for the 300 miles of highway between Oakland and Los Angeles. I was ready to return home to my dog, my job, and my destiny.

It was Tuesday. Three weeks and a day before I had surgery, specifically a “gender-affirming vaginoplasty,” which these days is euphemistically called “bottom surgery,” an awful phrase that makes me imagine British schoolboys describing their fathers’ colonoscopies. If it wouldn’t mean revoking my trans card, I’d advocate for a return to calling it “the surgery” with a hushed tone equal parts admiring of its gravity and salivating over its Jerry Springer titillation.

Nothing about Tuesday had been titillating. I woke up at 5 am and dilated, a three-time daily ritual of preserving my vaginal canal with heavy, color-coded, hard plastic dildos of increasingly intimidating diameter.

I showered and cleaned the “surgical site” (another euphemism, the least sexy thing I’ve ever heard a vagina called). While washing, I accidentally inserted the tip of my medical douche into my swollen urethra and popped two stitches with the pressure from the water.

Back in the bedroom, I proceeded to step on one of the many earrings I’d had to remove for the last two weeks of hyperbaric treatments. Jewelry was forbidden in the pressurized chamber, for its potential to spark and ignite the healing oxygen, flash-frying a steel tube full of medicated trans people.

I’d purchased a box of flat-back earrings from Amazon, cheap ones I wouldn’t worry about losing in the fog of Percocet and pain. I inspected the ball of my foot and found a silver butterfly happily pierced into my sole. I extracted it with a yelp. I decided it was a cursed object and threw it in one of the trash bags in the room, overflowing with used pads (puppy pads and maxi), paper towels, and diapers. Sopping up blood and body fluid had become a constant project since I’d gotten my catheter out and bandages off.

Breakfast took the form of tapioca pudding cups we’d purchased preop in case I got snackish during recovery. The first two cups were delicious, so I considered the third with “treat yourself” eyes. The pudding met my tongue with a carbonated, bitter sting of botulism and rot. I retched into the kitchen sink, brushed my teeth, and left for my final post-operative appointment with the surgeon’s nurse practitioner.

The light was never the same twice in two weeks of daily driving from Oakland to San Francisco. It would be a perfect city for painters if painters could afford to compete for rent against the tech bros conspiring to replace them with AI. Sunlight piercing the gray clouds cast dramatic spotlights on cargo ships, colorful house-crusted hills, and the pinnacle of the Bay Bridge.

Traffic was frustrating and painful, but too pretty to get upset about, and as I bounced up and down the hills, past encampments and Victorian dollhouses, I imagined living there in the city’s hippie, pre-AIDS prime, a young trans girl wandering from Richard Brautigan’s short stories to Armistead Maupin’s 28 Barbary Lane. I’m prone to fantasizing about being one of the fearless women living “stealth” like Tracey Norman, Janet Mock or Geena Rocero, in a time before trans people were quite so on the minds of the cis world. I like the feeling of pretending I could ever be so savvy, so smart, so brave.

Post-op medical commuting also provided a tour of my partner’s former apartment, favorite restaurants, and coffee shops - her life before me. Krista spent years in the Bay as a stand-up comic and trapeze artist, and something about giving a place to the version of her I’ve only seen in pictures makes my heart swell. She was wild in all the years I spent pursuing domesticity: a straight marriage, two kids, a suburban house, and 401K. It makes me feel special that despite my history of squareness, Krista thinks I’m worthy of being a character in her story.

Parking for the surgeon’s office shook me from my musings. I found a space between two Teslas three blocks away and waddled painfully to my appointment, feeling every step. The lobby of the building had been the stage for a huge scene between myself and a friend who’d flown from New York to help me recover. I’d felt too self-conscious to let Krista be the one to wipe me and empty my catheter bag. I turned down an offer of help from another trans girlfriend of mine who I love, but whose transition seemed so intimidatingly perfect from the outside that I felt ashamed to let her see me at my worst.

The help I accepted came from a funny, irreverent, punk internet friend who had been a mentor to me in early transition, patiently talking me down from many precarious ledges as transition blew up my life, my marriage, and my job. She was superhuman in the generosity of her deeds: feeding me, bathing me, lifting me on and off the toilet. But her sense of humor was incompatible with my vulnerability and pain: too many jokes too reminiscent of the people who’d hurt me the worst. I hated the feeling of being physically helpless, emotionally unable to hold my own.

I’d made a dramatic escape. When my friend attempted to accompany me into the doctor’s office for my first post-op, I told her she wasn’t welcome. When she insisted, I told her I’d call the police. Things went south from there. Normal people politely ignored the intra-trans screaming match blocking the path from the entry to the elevator. At one point, I compared my friend to my transphobic mother. Maybe she said something fucked up, too? I don’t remember. It was messy and chaotic as only trans women can be.

Upstairs, when the bandages and catheter were removed, and my new vagina was been being unveiled to me - I was not paying attention. I was on my phone texting my friend instructions to go back to New York, texting Krista for emotional support, and trying to find another place to stay - all while my iPhone battery slowly depleted.

It wasn’t until I’d checked into a Best Western with a parking lot full of 18-wheelers that I had a chance to see my new body. I was unable to sit, unable to walk, and had no place to go. All of my meds and supplies were at the Airbnb. I was too tired, drugged, aching, and depressed to face my friend. I booked a room close to the Airbnb just to have a place to lie down for a few hours while I waited for my friend to leave on a red eye. I made the cheapest possible reservation online, but it wasn’t available when I arrived. The manager upgraded me to a “bay view King Suite.”

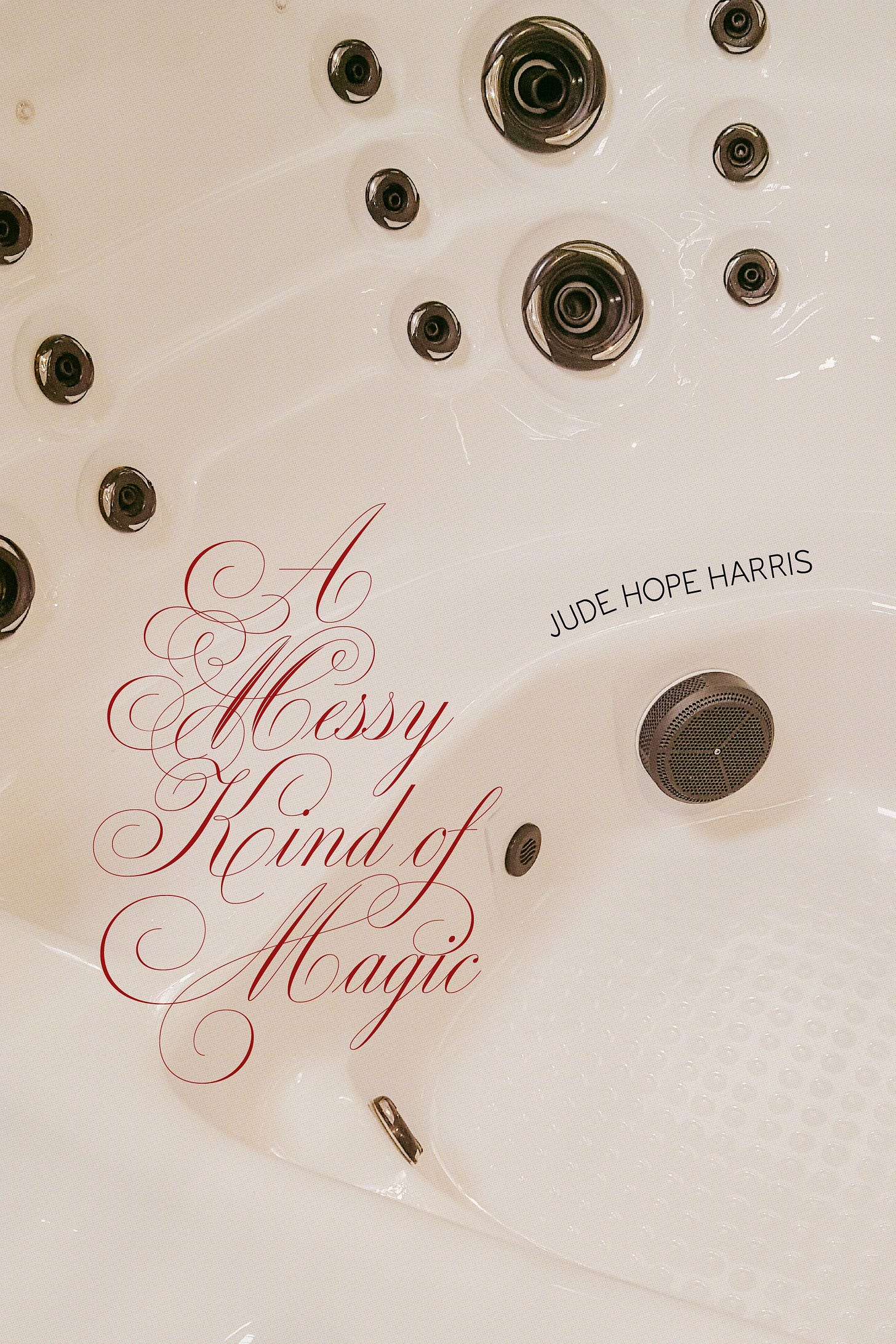

The room was huge, with a view that allowed guests to watch the sun setting over the water while keeping an eye on their trucks. It was beige and boring with a big bed and jacuzzi tub designed to fit 2-3 people. It was the kind of place where I imagine successful and sexually adventurous managers of transportation and logistics companies host orgies.

Embracing the seediness, I stripped gingerly in the party-sized bathroom. In the mirror, for the first time, I saw a body that looked like my home. I felt the presence of the divine: funny and insane and beautiful. The moment was saturated with grace. My soul and my flesh reconciled. Years of mutual unkindness and misunderstanding were forgiven.

Then I watched Dune on HBO, which turned into a nap.

Between the first appointment and the last, everything changed. Krista had flown home to LA after I was discharged safely from the hospital. She drove back to Oakland to care for me. I learned what it feels like to consider yourself worthy of the selfless love and care she gave me. My body, for its part, demanded the same of me and I learned, at least a little, to listen to its requests for rest and tenderness. And this surgery, always positioned to me as the biggest of big deals, started to seem like the opposite. Hadn’t I always been this way?

At my final appointment, the nurse practitioner inspected me with a speculum, snipped a few stitches and surplus flesh, cauterized my wounds, and approved me for travel home. I went back to the Airbnb and loaded my car while Krista picked up lunch in hers.

Continuing the chaos of the day, I accidentally let Pancake, Krista’s chihuahua, run away. We spent a half hour of total panic screaming her name before being guided to the home of a kind, semi-verbal old woman who had found Pancake scratching at her front door. She wouldn’t let us go until she’d shown us a framed snapshot of her chihuahua who had died a year before. Krista and the old woman hugged, bonded by their chihuahua love. Our trip was over.

Not long after, I was on the highway, winding past green, springtime hills dusted in yellow mustard flowers, past the reach of BART trains, into ranch land. I tried to reconcile the simultaneous feelings that my surgery was unremarkable and that I was returning a different person than the one who left.

The best I could do was this:

My earliest desire was one that I could not articulate and thought was impossible to attain. My soul cried out to be a girl, to be a woman. I imagined that it was a fairytale wish that could be granted if I just figured out the trick.

I prayed, at home and in the silence at church after communion. I put my hope into every unusually shaped rock, oversized acorn, comet passing, four-leaf clover, and birthday candle for years before I gave up. If my most important desire would never be realized, did any desire matter? I decided to play it safe and only nourished the normal ones: love, family, career. I grew up. I gave up on wishing and focused on working.

What did it mean that my wish had been granted? Magic, it turned out, didn’t look like it does in stories. It looked like womanhood with a thick trans accent. It looked like hours of arguing with insurance companies. It looked like the waiting rooms of doctor’s offices, surgical centers, electrologists, the DMV. It looks like food and flowers from friends.

In stories, magic is fast. In my life, magic had crawled. My wish took decades to be uttered in words that I could understand. It took years to manifest. Divinity not only works in mysterious ways, it works on its own schedule.

When I merged onto the 405, I drove fast, cranked Haim’s “Los Angeles” loud, and savored my love for my city. I was returning someone who was still defined by all her “normal” blessings: her family, her partner, her home, her career. And, yes, this me had a different body, throbbing with pain from the long drive. But that body didn’t feel like a new thing, really. What felt new was an expansive sense of possibility.

What other prayers might be answered if I opened myself to the circuitous paths they might take? What if every wish coming true were as messy and disruptive as this one? What if I embraced that, and kept wishing anyway?

Your story is quite beautiful and very poignant. Blessings and best to you. Let us hope that the current sexual madness will pass and a better world for all will evolve.

Every human being ever born is made in the Imago Dei, and their intrinsic freedom can never be abridged.

I am very moved by your determination and strength.

May God be always with you in your journey.

Fred